Part Two – The leap from non-paid to paid science writing via opinion pieces.

Most advice I’ve seen for aspiring/newbie science writers recommends they start pitching short “front of book” news stories. The kind of work where editors require a quick turnaround and the articles are straightforward to pull together. Writers therefore don’t need an extensive portfolio of paid work, just samples that show they’re familiar with the genre.

I stumbled through another entry point: the Op-Ed.

The Source.

Okay, another useful bit of freelance science writing career advice I have: Twitter should be your weapon of choice. Plenty of online media have Pitch/Submission Guidelines on their main website (once you’ve scrolled to the bottom), but Twitter is where a lot of editors call for pitches. Heck, you can even find the names, email addresses and remits of editors, if they aren’t listed elsewhere.

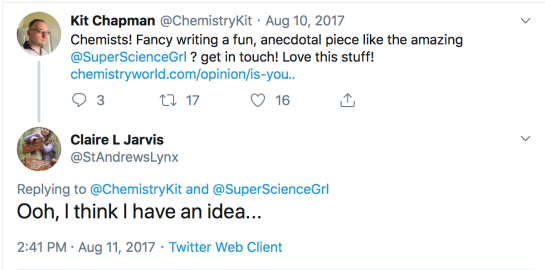

Anyway, in August 2017 I saw Nessa (@SuperScienceGrl) – a fellow #ChemTwitter citizen, at the time fresh out of grad school and starting her industrial chemist career – write an op-ed/humour column for Chemistry World magazine [1]. After reading her column I was slightly jealous: deservedly so, because it was a great read. This piece marked an directional shift in ChemWorld’s ‘Last Retort’ column: its editor Kit Chapman[2] was steering the column away from “interesting historical tales” to “fun everyman slices from scientist life”.

I saw Kit’s call for pitches (see above) right after Nessa’s article was published. Since hers was the first column under the new direction I had the advantage of being able to pitch almost anything knowing it hadn’t already been taken…but with little guidance from previous columns about what was acceptable/expected.

The Pitch

It didn’t take too long to come up with an idea (lack of raw ideas is rarely a problem for me, but I need to get better at refining & targeting them to the right publications). I was aiming for a universal experience that every chemist – be they a research professor, industrial scientist or student – could relate to. But it also had to be something humorous that no one had written much about before. I went with thesis acknowledgements.[3]

I’ll talk in my next blog post about what you shouldn’t do when writing opinion, but this ~700 word piece was easy to fill out and didn’t require straining to meet the word count.

Perspectives and opinion pieces are a good entry into science writing. They’re less competitive/elusive than full-length features, and background expertise with the subject matter is often an acceptable substitute for paid writing clips. From what I’ve seen, pay for an opinion piece is on par with pay for a similar-sized news story. Editorial oversight and journalistic rigour vary between outlets, but some publications (e.g. Undark) put their opinion pieces through the same fact-checking wringer as their Features and News. All you need is an opinion and evidence to back it up. The Open Notebook has a guide to writing opinion you may wish to consult.

Anyway, the Last Retort column was where I landed my first paid writing assignment. Now I could angle towards writing features…

Footnotes

[1] Nessa is still going strong at the science writing and is now a Chemistry World featured columnist. I’m not the only one who used this route!

[2] Kit Chapman has since moved on from Chemistry World. Check out his debut book ‘Superheavy: Making and Breaking the Periodic Table‘ – it’s an excellent vehicle for his writing and wit.

[3] This was an idea I had to sit down and think about (“Hey, why don’t I write…”), then I needed to think some more about what I’d include and its structure. In contrast, I wrote a particularly sassy entry in my private diary about an eventful group dinner at a chemistry conference – several months later I converted that diary entry into a Last Retort column with minimal adjustments.